Chicago Film Fest, Dispatch #3: The Brutalist, Memoir of a Snail, and a new Robert Zemeckis experiment

My final check-in from the 60th Chicago International Film Festival

Welcome to Girl Culture, the newsletter where Caroline Siede examines pop culture, feminism, and more. You can learn about Girl Culture’s mission here and support here.

The final few days of the Chicago International Film Festival brought with them some of the buzziest premieres of the entire fest. And they also reminded me that it can be really exhausting to cover a film festival, at least when you’re also trying to keep up with your regular freelance workload at the same time. All told, I saw 12 features, one short, and one “keynote conversations” across the 12 days of the festival (you can find my previous fest dispatches here and here). And while I certainly could’ve done better if I were attending on an actual paid assignment, I’m proud of how much I managed to see on Girl Culture’s behalf.

I’m also very impressed with the public moviegoers who turned up for the fest this year. Chicago cinephiles were out in full force for the artier, more abstract films—from a Zambian dramedy about cycles of abuse to a 3.5-hour film about brutalist architecture. And it was a delight to sit alongside them as the festival wrapped up its programming. Here are four final reviews to end this dispatch series. You can expect all of these movies to either be major players this awards season or at least be a big part of the “best/worst of the year” conversation.

The Brutalist (an Oscar-favorite historical epic hitting theaters Dec 20)

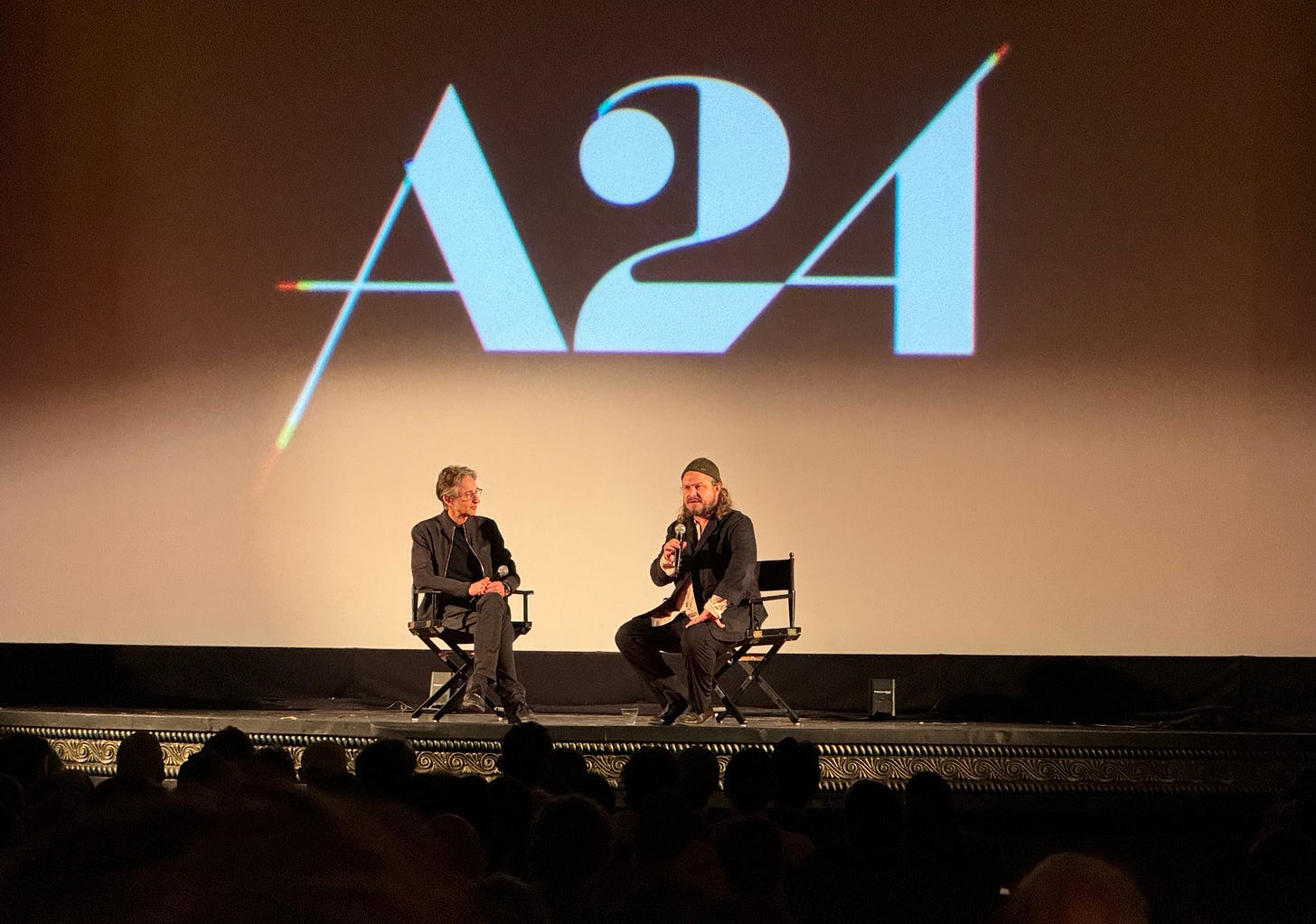

Of all the premiere screenings I attended, this one definitely felt like the “event” of the festival. Unfortunately, that means I watched it crammed into a tiny Music Box seat between two men who really didn’t understand the concept of personal leg space. (Talk about brutalism, am I right?) And given that it’s a whopping 3.5 hours long, that was no small feat. I’m glad I did though because hearing director/co-writer Brady Corbet discuss the film really helped contextualize both what did and didn’t work about it for me.

A buzzy Oscar-favorites ever since it premiered at Venice, The Brutalist stars Adrien Brody as László Tóth, a Hungarian-Jewish architect who emigrates to the United States in 1947. The first half of the decade-spanning film follows László’s early, hopeful immigrant experience while the second explores his fraught relationship with the American Dream (there’s a 15-minute intermission in-between). And while you’d be forgiven for assuming László is a real-life person or that this movie is based on some kind of epic historical novel, the story is simply born out of Corbet’s desire to make a movie that explores “post-war psychology and post-war architecture.”

Corbet also noted that the movie is difficult to discuss in Q&As because it’s distinctly cinematic in way that feels “inexpressible” in words, and he really hit the nail on the head there. I found the first half of The Brutalist wildly compelling in ways that are hard to sum up in a review. There’s something about its wry sense of humor, its methodical pacing, its gorgeously composed shots, Brody’s stellar central performance, and the film’s keen eye for the details of human behavior that make it incredibly gripping to watch, even though not a ton happens plot-wise. (László gets swept up into the world of a wealthy industrialist played by Guy Pearce, who first loathes and then loves his modern architectural style.)

Sadly, the second half was way more uneven to me—partially because the pacing starts to feel overly indulgent as the film takes some dark turns, but mostly because I didn’t love the casting or writing of László’s wife Erzsébet (Felicity Jones), who finally reunites with her husband after being separated from him during the Holocaust. Corbet explained that he wanted The Brutalist to slowly reveal itself to be a love story, and my disconnect from the Erzsébet character probably explains why I felt so disconnected from the second half of the film as a whole.

Still, the sheer ambition of what Corbet is trying to do with this American immigrant epic gives the film an innate power, even if it never quite adds up to more than the sum of its parts. There’s a boldness to both the small moments and the big ones. Like a piece of brutalist architecture, The Brutalist may be impenetrable, but it’s certainly impactful.

Grade: B+

On Becoming a Guinea Fowl (a Zambian A24 dramedy hitting theaters in 2025)

On Becoming a Guinea Fowl was one of the buzzy hits of this year’s Cannes Film Festival, so I was very excited to get the chance to see it on a big screen. The second feature from I Am Not a Witch director Rungano Nyoni, the film opens with a darkly funny, vaguely surreal sequence in which a young Zambian woman named Shula (Susan Chardy)—decked out in an elaborate Missy Elliot costume—calls her father to say she’s found her uncle dead on the side of the road. She doesn’t seem particularly upset about it, though, nor does her ostentatious cousin Nsansa (Elizabeth Chisela), who joins her shortly after. But while this could be the set-up for a murder mystery, Nyoni unravels a different kind of investigation. The nature of Uncle Fred’s death is never in question, but his legacy within the family very much is.

While On Becoming a Guinea Fowl pointedly explores divides across gender, generation, and class, it’s ultimately most interested in the power of community justice to heal those divisions. Guinea fowls, we’re told, are the alarm system of the savanna—warning other animals when a predator is approaching. As Shula’s family go about mourning Fred and sweeping the dark side of his past under the rug, Shula must decide whether she wants to remain a silent observer or finally speak out, both for herself and for others.

On Becoming a Guinea Fowl is no maudlin “message movie,” however. Nyoni operates in a dreamier, more impressionistic key, capturing the way Fred’s sisters obsess over the “correct” way to mourn his death, even as their daughters are clearly reeling from a different kind of trauma. There are moments where the film feels like it’s going to barrel into full-on magical realism, though it never quite does. When it comes to the subtle (and not so subtle) ways in which patriarchy operates, On Becoming a Guinea Fowl can be both drily funny and deeply harrowing—sometimes all at the same time.

For international audiences, the film also offers a fascinating glimpse into Zambian mourning rituals and Zambian social tensions more broadly. But for as much as this story is rooted in the specific cultural traditions of its Central African setting, it also speaks to universal truths about who we forgive and who we ostracize. We’ve all heard (or lived through) real-life stories of families protecting their problematic men over the safety of their daughters. On Becoming a Guinea Fowl is a slow-burn battle cry for a new way forward.

Grade: B+

Memoir of a Snail (an R-rated animated fable in select theaters now)

If two films constitute a trend, then animated stories of melancholy mollusks are really having a moment. On the heels of Marcel the Shell with Shoes On (my favorite film of 2021) comes this quirky Australian animated feature about a lonely girl with a passion for snails. Be warned however: While Marcel could be enjoyed by the whole family, Memoir of a Snail is an R-rated affair full of dark plot twists, sexual references, and more claymation boobs than you probably ever expected to see in your life time.

Indeed, it’s the contrast between the whimsical animation style and the dark subject matter that makes Memoir of a Snail such a compelling curio. Succession star Sarah Snook lends her voice to leading lady Grace Pudel, a shy, introverted young woman growing up in 1970s Melbourne with her twin brother Gilbert (Kodi Smit-McPhee) and their paraplegic father. But when tragedy strikes and the family is separated, Grace finds herself coming of age in a lonely world with only her pet snails and an eccentric octogenarian named Pinky (Jacki Weaver) as friends.

A moving, off-color story about hope in the face of suffering, Memoir of A Snail is above all a love letter to the wallflowers and homebodies among us; the people who sometimes feel more like snails curled up inside their shells than flesh-and-blood human beings. Despite the inherent whimsy of Grace’s animated world, her problems are more relatably human than most animated heroines have to deal with: anxiety, self-sabotage, grief, and depression, all beautifully captured in Snook’s empathetic voice performance. But while writer/director Adam Elliot puts his heroine through the wringer with a relentless string of tragedies, this is ultimately a story of perseverance and hidden inner strength.

With a visual style that calls to mind Henry Selick’s Tim Burton collaborations (James and the Giant Peach, The Nightmare Before Christmas) by way of The 400 Blows, Memoir of a Snail has a savvy understanding of the power of animation. If this story were live action, it would be too much to bear, but if it weren’t so tragic, it would be just another charming animated fable. Instead, Memoir of Snail charts its own snail trail—boldly proclaiming that animated stories can be heavy and heavy stories can also be hopeful celebrations of life.

Grade: A-

Here (a Forrest Gump reunion hitting theaters Nov 1)

The fest’s closing night screening began with Robert Zemeckis accepting the Founder’s Legacy Award, although it was 82-year-old CIFF founder Michael Kutza who really stole the show by joking that not many people get a founder’s award from the “fucking founder” himself. I’ve always found Zemeckis to be a curious figure within film history. Though Back to the Future, Who Framed Roger Rabbit, Forrest Gump, and (to a certain generation) The Polar Express are firmly baked into the modern American cinema canon, I don’t think Zemeckis himself has the household name recognition of a Spielberg or a Scorsese. Perhaps that’s because he’s spent so much of the latter half of his career making effects-heavy oddities like Beowulf and Welcome to Marwen.

Obviously, CIFF-goers were very excited to see him, though, and I think a lot of us were disappointed he didn’t stick around for a post-screening Q&A about his new film Here. Given how disastrously the film had been reviewed at its AFI Fest premiere the day before, however, I get his impulse to cut and run. (Or maybe he doesn’t just like Q&As, I’m not sure.) But, to me, Here is less of an all-out disaster than a movie with a fascinating central conceit and fairly subpar execution.

The high-concept premise is that Zemeckis locks his camera in one spot and doesn’t move it for the entire film—from the time of the dinosaurs to the COVID era. Instead, while the camera stays still, the film hops around in time to show how that space was once a verdant forest for Native Americans, a road for Colonial residents, and eventually a living room for four different generations of families, the main one being Tom Hanks and Robin Wright as a young Baby Boomer couple coming of age in the latter half of the 20th century. (We also see a worried wife in the 1910s, a kooky couple in the 1930s, Hanks’ parents in the late 1940s, and a modern-day family living through 2020.)

Here is part of what I’m dubbing “This Is Us cinema”—movies that tell simple domestic stories but use the passage of time in way that makes those stories thematically richer. I’m an absolute sucker for this kind of sentimental celebration of the human experience, so there was a lot about Here that worked for me on a conceptual level. (Yes, tell me how even though different generations lived different kinds of lives, we’re all fundamentally the same!!) But, unfortunately, a weak screenplay, clunky de-aging work (Hanks and Wright start the movie playing 15-year-olds), and garish digital effects kept me from ever truly getting sucked into the story—though I did hear a fair share of muffled sobs around me as the movie reached its tearjerking conclusion.

I was invested enough in all the various intersecting storylines that I never felt bored, but the locked off camera winds up feeling more distancing than unifying. The movie gets some occasional visual flourishes thanks to a comic book panel effect that allows images from various timelines to briefly overlap—a style pulled from Richard McGuire’s 2014 graphic novel of the same name. But the whole thing mostly winds up feeling like a play with not-that-interesting characters. If anything, Here made me appreciate that what This Is Us did so effortlessly really does take a deft hand to pull off. Zemeckis gets halfway there, but ultimately leaves us nowhere. Still, as cinematic experiments go, at least this one showed me something I’d never quite seen before.

Grade: C+

Other stuff I’ve worked on lately: I reviewed the second season of Netflix’s zippy political drama The Diplomat and explored the moving new documentary The Remarkable Life of Ibelin for The Daily Beast. Plus I wrapped up my weekly coverage of Agatha All Along over on Episodic Medium.